Apa yang mereka lakukan sekarang, kawan-kawanku yang melakukan "perjalanan" bersamaku di kelas yang sama di "gerbong kereta"?

Akira Takahashi

Takahashi, yang memenangkan semua hadiah di Hari Olahragam tidak pernah tumbuh lebih tinggi. Tapi, dengan nilai-nilai amat bagus, dia berhasil diterima di SMU yang di Jepang terminal karena tim rugby-nya.

Dia melanjutkan ke Universitas Meiji dan meraih gelar insinyur listrik. Sekarang dia menjadi manajer personalia di perusahaan elektronik besar dekat Danau Hamana di Jepang tengah. Wataknya yang periang dań kepribadian yang menarik pastilah sangat membantu dałam tugasnya.

Ketika menggambarkan hari pertamanya di Tomoe, Takahashi berkata dia langsung merasa nyaman ketika melihat anak-anak lain dengan cacat tubuh. Dia juga tidak malu lagi ketika mendapat giliran berdiri di depan anak-anak lain waktu makan siang untuk berpidato.

Dia bercerita kepadaku bagaimana Mr Kobayashi menyemangatinya untuk melompati kuda-kuda yang lebih tinggi daripada dirinya. Mr Kobayashi selalu meyakinkannya bahwa dia bisa melakukannya, meskipun sekarang dia menduga Mr Kobayashi telah membantunya melompat (tepat pada saat terakhir, dan membiarkan dia berpikir bahwa dia mampu melakukannya dengan kekuatannya sendiri).

Mr Kobayashi memberinya rasa percaya diri dan memungkinkan dia mengenali kegembiraan yang tak terkatakan ketika berhasil mencapai sesuatu.

Miyo-chan (Miyo Kaneko)

Putri ketiga Mr Kobayashi, Miyo-chan, lulus dari Departemen Pendidikan Kolese Musik Kunitachi dan sekarang mengajar musik di sekolah dasar yang merupakan bagian dari kolese itu. Seperti ayahnya, dia sansat suka mengajar anak-anak kecil.

Sejak Miyo-chan berusia tiga tahun, Mr Kobayashi telah mengamati bagaimana putrinya itu berjalan dan menggerakkan badannya mengikuti irama musik, begitu pula waktu belajar bicara, dan itu sangat membantu Mr Kobayashi dalam mengajar anak-anak.

Sakko Matsuyama (sekarang Mrs. Saito)

Sakko-chan, Anak Perempuan bermata lebar yang mengenakan rok kelinci pada hari aku mulai bersekolah di Tomoe, masuk ke sekolah yang dimasa itu sangat sulit dimasuki anak perempuan (sekolah yang sekarang dikenal sebagai SMU Mita).

Dia lalu melanjutkan ke jurusan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Kristen Wanita, Tokyo, dan menjadi instruktur bahasa Inggris di YWCA. Sampai sekarang dia masih bekerja di sana. Dia menggunakan pengalamannya di Tomoe dalam acara-acara perkemahan musim panas YWCA.

Taiji Yamanouchi

Tai-chan, menjadi salah satu ahli Fisika Jepang yang ternama. Dia tinggal di Amerika. Dia lulus sebagai sarjana Fisika jurusan Sains, Universitas Pendidikan Tokyo. Setelah meraih gelar master, dia pergi ke Amerika dengan beasiswa dari Fulbright dan meraih gelar doktornya lima tahun kemudian di University of Rochester.

Dia masih disana, melakukan riset mengenai eksperimen fisika energi tinggi. Sekarang dia bekerja di Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory di Illinois, laboratorium terbesar di dunia, dan menjadi asisten direktur. Laboratorium riset itu terdiri atas para sarjana paling pandai yang berasal dari lima puluh tiga Universitas paling ternama di Amerika. Laboratorium itu juga merupakan Organisasi raksasa dengan 145 ahli fisika dan 1400 staf teknis. Anda bisa bayangkan betapa jeniusnya Tai-chan. Laboratorium itu menarik perhatian dunia lima tahun yang lalu kotika berhasil memproduksi sinar energi Tinggi berkekuatan 500 miliar elektron volt.

Baru-baru ini, Tai-chan, bekerja sama dengan professor dari Columbia University, menemukan sesuatu yang disebut upsilon. Aku yakin, sustu hari Tai-chan akan mendapat Hadiah Nobel.

Tai-chan menikah dengan gadis berbakat yang lulus dengan nilai-nilai bagus di bidang matematika dari University of Rochester. Dengan otak seperti itu, Tai-chan mungkin akan melaju pesat tak peduli sekolah dasar seperti apa yang pernah dimasukinya.

Tapi menurutku, sistem pendidikan di Tomoe yang membiarkan anak-anak mengerjakan pelajaran menurut urutan yang meraka inginkan, mungkin telah membantu mengembangkan bakatnya. Aku tidak ingat dia melakukan hal lain selama jam pelajaran selain membuat percobaan dengan pembakar alkohol dan tabung-tabung reaksi atau membaca buku yang tampaknya sangat sulit mengenai sains dan fisika.

Kunio Oe

Oe, Anak yang menarik kepangku, sekarang menjadi ahli anggrek spesies Timur Jauh yang paling disegani di Jepang, yang benih hasil silangnya bisa berharga puluhan ribu dolar.

Dengan keahliannya yang sangat khusus itu, Oe bahkan dimintai bantuan dimana-mana. Dia sering sekali melakukan perjalanan ke segala penjuru Jepang. Dengan susah payah aku berhasil bicara dengannya lewat telepon, di antara perjalanan-perjalanannya. Berikut ini obrolan singkat kami:

"Kau sekolah di mana setelah Tomoe?"

"Aku tak sekolah di mana-mana."

"Kau tidak sekolah di sekolah lain? Tomoe satu-satunya sekolahmu?"

"Ya."

"Astaga! Tidakkah kau bersekolah di sekolah lanjutan?"

"Oh ya, aku sekolah beberapa bulan di SMP Oita ketika aku diungsikan ke Kyushu."

"Tapi, bukankah menyelesaikan sekolah lanjutan itu wajib?"

"Benar. Tapi aku tidak selesai."

Astaga! Santai benar dia, pikirku. Sebelum perang, ayah Oe punya perkebunan tanaman hias yang sangat luas yang memenuhi sebagian besar wilayah yang disebut Todoroki di barat daya Tokyo, tapi semua itu dihancurkan bom. Sifat Oe yang tenang terasa sekali sepanjang sisa percakapan kami ketika dia mengalihkan pembicaraan.

"Kau tahu bunga apa yang paling harum? Menurutku bunga anggrek musim semi Cina (Cymbidium virescens). Tak ada parfum yang bisa menyamai keharumannya."

"Apa angrep itu mahal?"

"Ada yang mahal, ada yang tidak"

"Seperti apa bunganya?"

"Yah, tidak mencolok. Malah tidak istimewa. Tapi itulah daya tariknya."

Gaya bicaranya sama sekali tidak berubah, masih seperti etika bersekolah di Tomoe. Mendengarkan suara Oe yang santai, aku berpikir, dia sama sekali tidak peduli, walaupun tak pernah menamatkan sekolah lanjutan! Dia selalu melakukan apa yang ingin dilakukannya dan yakin pada dirinya sediri. Aku sangat terkesan.

Kazuo Amadera

Amadera, yang mencintai binatang, jika sudah dewasa ingin jadi dokter Hewan dan Punya Tanah pertanian. Sayangnya, ayahnya tiba-tiba meninggal. Dia terpaksa mengubah rencana hidupnya secara drastis. Dia keluar dari Facultas Kedokteran Hewan dan Peternakan, Universitas Nihon, untuk bekerja di Rumah Sakit Keio. Sekarang dia bekerja di Rumah Sakit Pusat Pasukan Beladiri dan memegang jabatan yang ada hubungannya dengan pemeriksaan klinis.

Aiko Saisho (sekarang Mrs. Tanaka)

Aiko Saisho, yang adik kakeknya adalah Laksamana Togo, dipindah ke Tomoe dari sekolah dasar yang dikelola Aoyama Gakuin. Aku selalu mengingat dia di masa itu sebagai Anak Perempuan yang Tenang dan santun. Mungkin dia memang tampak begitu karena telah kehilangan ayahnya (seorang mayor di Resimen Garda Ketiga yang teras dalam Perang Manchuria).

Setelah lulus dari SMU Kamakura khusus untuk murid Perempuan, Aiko menikah dengan seorang arsitek. Sekarang setelah kedua putranya dewasa dan sibuk berbisnis, dia menghabiskan banyak waktu luangnya dengan menulis puisi.

"Jadi kau melanjutkan tradisi bibimu yang termahsyur sebagai penyair wanita yang mendapat penghargaan dari Kaiser Meiji!" kataku.

"Oh, tidak," Katanya sambil tertawa malu.

"Kau tetap rendah hati seperti ketika bersekolah di Tomoe," kataku, "dan tetap anggun". Mendengar itu dia mengelak dengan berkata, "Kau tahu, tubuhku masih sama dengan ketika aku memainkan Benkei!"

Suaranya membuatku berpikir betapa hangat dan bahagianya rumah tangganya.

Keiko Aoki (sekarang Mrs. Kuwabara)

Keiko-chan, yang punya ayam bisa terbang, menikah dengan guru sekolah dasar yang dikelola Universitas Keio. Dia Punya satu anak perempuan yang sudah menikah.

Yoichi Migita

Migita, anak laki-laki yang selalu berjanji akan mebawakan kue pemakaman, menjadi sarjana holtikultura, tapi dia lebih suka menggambar. Jadi dia bersekolah lagi di moleste dan lulus dari Kolese Seni Mushashino. Sekarang dia mengelola perusahaan desain gratis miliknya sendiri.

Ryo-chan

Ryo-chan, si penjaga sekolah, yang pergi ke medan perang, kembali dengan Selamat. Dia tak pernah melewatkan acara reuni siswa Tomoe setiap tanggal tiga November.

Tetsuko Kuroyanagi

When this national treasure-level host and writer stepped onto the stage with her iconic onion head, people couldn't believe that the woman in front of her was 86 years old.

Tetsuko Kuroyanagi, this name is unfamiliar to many people, but you must know the classic children's literary work "The Little Girl at the Window". "The Little Girl at the Window" is the highest-selling publication in Japan's history. The simplified Chinese version has sold more than 11 million copies, and it ranks among the best-selling books all year round.

Everyone is attracted by the interesting Ba Academy and the considerate principal, but what many people don't know is that this story is the true experience of the author Tetsuko Kuroyanagi. Now this woman has broken the Guinness record for the life of the show she hosted.

In 1933, Kuroyagi Tetsuko was born in a family full of literary temperament. His father is the principal violinist of the National Symphony Orchestra, and his mother is a famous essayist.

Tetsuko Kuroyanagi is naturally free and lively, because of loose discipline and excessive playfulness, which often affects classroom discipline.

(Tetsuko and mother)

After repeated ineffective teaching, Kuroyagi Tetsuko became a problematic student in the eyes of the teacher, and was eventually persuaded by the principal to leave.

she had no choice but to be regarded as a hyperactive child, and was sent by his parents to the "Ba Gakuen", a school specializing in the education of mentally handicapped children.

Ba Academy is a magical school, where there is a tram classroom, and lunch is "smell of the sea" and "smell of the mountain".

(Tram Classroom at Ba Academy) In Ba Academy, Tetsuko, who was not loved by the teacher, met Mr. Kobayashi who changed her life. At the first meeting, The Principal listened quietly to Tetsuko's speech for 4 hours. Tetsuko felt "understood" for the first time.

Principal Kobayashi used a special education method to let the children in the Ba Academy who were rejected by ordinary schools learn to understand and love. He also used his own way to protect the children's self-confidence and innocence.

He always felt that “it is absolutely necessary for children to express their ideas clearly, freely, and without shyness in front of others in the future.” Under this kind of protection, Tetsuko grew up and became a special person who dared to express his own opinions and understood others.

After adulthood, Tetsuko Kuroyagi, who had excellent academic studies, was admitted to the Tokyo Conservatory of Music to study vocal music and studied Chinese at the Keio University Faculty of Letters, one of the highest schools in Japan.

(Young Kuroyagi Tetsuko)

In a TV show, Tetsuko Kuroyagi stood out from 6,000 contestants. As one of 13 shortlisted candidates, he became the first batch of actresses on Japanese TV screens.

As the host of children's radio programs, Tetsuko Kuroyanagi, who was lively and smart in nature, became a hit, and he took over 7 variety shows in one breath and became a well-known artist in Japan at that time.

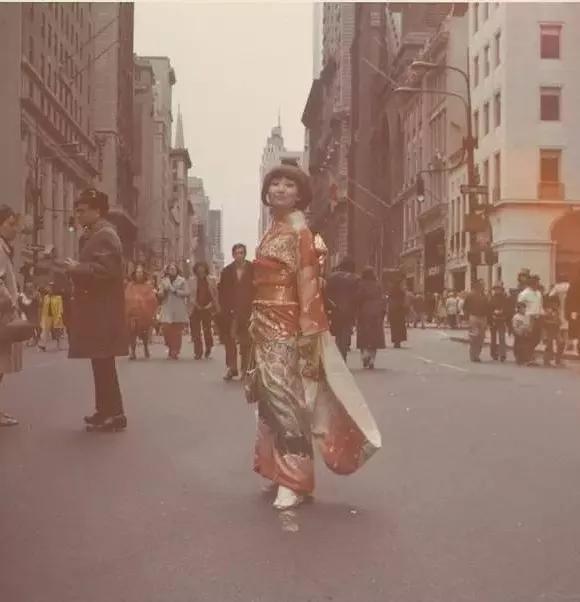

At the age of 38, Kuroyanagi Tetsuko, who was in a prosperous career, made an amazing decision: to study in the United States.

Even though she is already very popular, she finds that there is still a certain gap between her performance and professionalism. She wants to make up for her shortcomings through learning.

Very often, choice determines the height of a person's future.

A few years of advanced studies not only improved Tetsuko's acting skills, improved her English, and the outside world, which broadened her vision and made her clearer about her future direction. (Kuroyanagi Tetsuko on the streets of New York)

Living independently in New York, Tetsuko, who has her own unique thoughts, who dares to speak and speaks, was attracted by the producer and invited her to host a live-action talk show.

From then on, people saw a lively and sharp Kuroyanagi Tetsuko with an "onion head" reappearing on the screen. The talk show "Tetsuko's House" hosted by her has been broadcast continuously for 40 years, with more than 10,000 episodes, and has become the longest-lived talk show recognized by Guinness.

All famous characters in Japan have appeared on her shows, and foreign stars also like to participate in her shows. Tetsuko still didn't change her innocence. During the live broadcast, he took out candy from the "onion" to entertain the child star, or when he went abroad, he took out his passport from the onion and made the customs laugh.

People like her more, in addition to her humor, but also her wisdom.

The childhood experience of Ba Academy has a profound influence on Kuroyagi Tetsuko. In 1981, she recorded her childhood experiences and made "The Little Girl at the Window".

Generations of readers have been moved by Ba Academy and Principal Kobayashi, including Grant at the time, UNICEF Secretary-General.

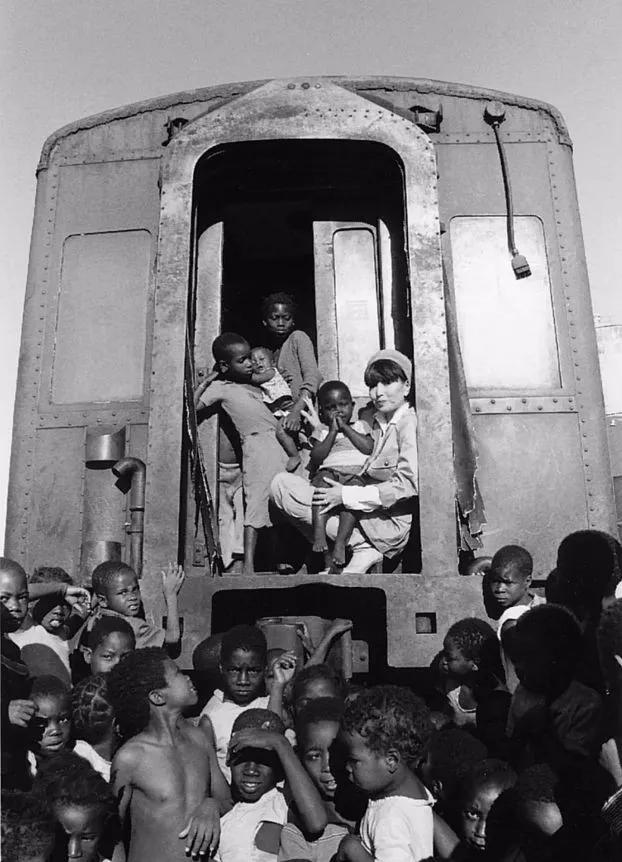

After watching "The Little Girl at the Window", Grant felt that Tetsuko Kuroyanagi was the person who knew children best. After discussion, Tetsuko Kuroyanagi was appointed as the UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, and she is also the fourth goodwill ambassador in the world.

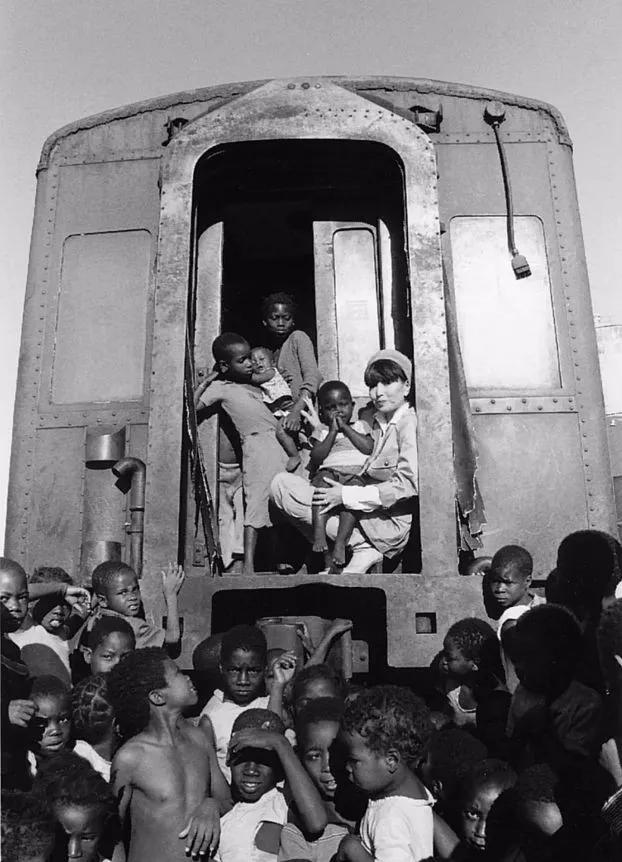

Tetsuko, who has always been concerned about public welfare undertakings, has truly shouldered this responsibility. Since 1984, Kuroyanagi Tetsuko has traveled across three continents and 29 countries and regions in the past thirty years.

From Tanzania, which is deeply invaded by poverty, to Rwanda, where civil wars are frequent, to Haiti and Indonesia, which have suffered from tsunamis and earthquakes.

She ate and lived with the local poor children, feeling their fear hidden in the depths, and conveying the situation of children in poverty-stricken areas to the people of the world through images and texts.

Thanks to her efforts, more people began to pay attention to these children in need.

She donated nearly 7.8 billion yen (equivalent to about 500 million yuan) of huge donations to solve their food and clothing problems, received health vaccinations, and rescued a large number of dying children from the hands of death.

In 2000, she visited Liberia on the eve of the war and suggested to the local government many effective measures to protect the personal safety of the children.

"You know that saving a child's life is not easy, but I think, even if only one child can be saved, we are one step away from despair."

The situation of children in poverty and war deeply touched her. There are many children on this planet who are struggling to survive while worrying about their family and their own destiny. Only a small percentage of children can drink clean water, eat a full meal, get vaccinated vaccination, and receive education.

"What is true happiness?" When all the children on the earth can live with peace of mind and hope, it can be said to be true happiness. Thinking about it this way, the moment I felt "so happy" when I stayed at home on that rainy night when I was a child, it can be said to be true happiness! (From "What is Real Happiness")

Nowadays, although she has never been married and has no children, she has helped millions of suffering children. Not only that, she is also working hard to tell the children around her to cherish the happy life in front of her.

(Lovely old lady)

Today, Tetsuko Kuroyanagi, who is nearly 90 years old, is still working hard.

She hosts programs and listens to other people's stories. She runs through poverty and misery to spread power. More importantly, she still maintains a childlike innocence towards life.

She loves giant pandas madly, owns all kinds of pandas around, and carries them with her.

Not only that, but also participate in panda protection activities and promote giant pandas.

After registering ins as an "Internet addiction elderly", she likes to post funny and fun photos in life like a young man to share with everyone.

This lovely old lady has attracted the attention of many fans.

"Eighty-year-old may seem a bit scary to say, but imagine that there are four 20-year-old girls living in the body."

Tetsuko Kuroyanagi, who always has a childlike innocence, often tells people around him, women, no matter how old they are, they must keep themselves beautiful. Until now, she has painted exquisite makeup every time she shows up, dressed in fitting clothes, and will always show her beautiful side to the public.

Thinking of a sentence in "The Little Girl at the Window",

"The most terrible thing in the world is that you have eyes but you can't find beauty, ears but you don't appreciate music, and a heart but you can't understand what is true. You won't be moved or full of passion."

Tetsuko Kuroyanagi tells us that a woman who is independent in her heart, with love and innocence, will never grow old.

(Source)